The Customer Progress Canvas: A Contextual Theory of Value Creation and Product Design

- Hani W. Naguib

- Dec 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Abstract

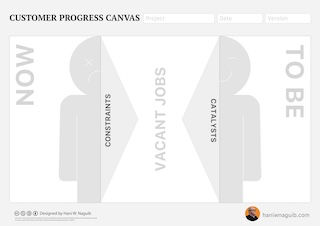

The Customer Progress Canvas (CPC) is a conceptual and practical framework designed to help teams understand customers not as static personas with problems, but as dynamic actors attempting to make progress within specific contexts. Rooted in Jobs-to-Be-Done theory, design thinking, cognitive psychology, and contextual inquiry, the CPC reframes product design from problem–solution matching toward progress-oriented value delivery. This article outlines the theoretical foundations, logical structure, and design rationale behind the CPC, positioning it as a synthesis tool that operationalizes customer progress in real-world innovation settings.

1. The Limits of Problem-Centric Thinking

Much of contemporary product and startup thinking is built on a problem–solution paradigm. Popularized by Lean Startup methodology (Ries, 2011), teams are encouraged to identify customer problems, validate their severity, and design solutions to solve them. While this approach has brought discipline to early-stage experimentation, it has also revealed structural limitations.

Empirical evidence consistently shows that a significant percentage of product failures are attributed to “no market need” (CB Insights, 2023). This failure persists despite teams following problem validation rituals. The paradox suggests that problem identification alone is insufficient for understanding why customers adopt—or reject—products.

Academic research supports this critique. Christensen et al. (2016) argue that customers do not simply buy products to solve problems; they “hire” products to make progress in their lives. Problems are symptoms, not the underlying driver of choice. What matters is the progress a customer is trying to achieve, given their circumstances, constraints, and alternatives.

The CPC begins where problem-centric models stop: with progress in context, not abstract needs.

2. Customer Progress as the Unit of Analysis

2.1 Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD) as the Core Foundation

The intellectual backbone of the CPC is Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD) theory. Originating from Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation (Christensen, 1997), JTBD reframes demand as situational rather than demographic. Customers are not bundles of attributes; they are actors navigating moments of struggle and aspiration.

In JTBD theory:

A job represents progress the customer is trying to make

The hiring decision is context-dependent

Competing solutions include habits, workarounds, and non-consumption

However, while JTBD excels at explaining why customers choose solutions, it often lacks a design-ready structure that helps teams translate insight into product decisions. The CPC extends JTBD by decomposing “progress” into observable, researchable components.

3. Context as a First-Class Variable

3.1 Contextual Inquiry and Situated Action

The CPC is heavily influenced by contextual inquiry (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1998) and the theory of situated action (Suchman, 1987). These bodies of research argue that human behavior cannot be understood outside the context in which it occurs.

Traditional personas freeze customers in time. They describe who the customer is, but not:

Where they are

What triggered action

What constraints shape decisions

What trade-offs are being made in the moment

The CPC treats context as the starting point, not an afterthought. Context includes:

Temporal conditions (time pressure, life phase)

Environmental constraints (location, tools, access)

Social forces (expectations, norms, power dynamics)

Emotional states (anxiety, hope, urgency)

This aligns with Gibson’s theory of affordances (1979), which argues that environments offer or restrict actions depending on the actor’s capabilities and perception. Products succeed not because of features, but because they fit the affordances of the customer’s context.

4. Progress Is Multi-Dimensional

4.1 Functional, Emotional, and Social Progress

Following the work of Christensen et al. (2016) and Norman (2004), the CPC explicitly recognizes that progress is not purely functional.

Customers make progress across three intertwined dimensions:

Functional: accomplishing a task or outcome

Emotional: reducing anxiety, gaining confidence, feeling in control

Social: signaling identity, belonging, or status

Many product failures occur when teams optimize one dimension while ignoring the others. For example, a product may be functionally superior but emotionally intimidating or socially misaligned.

The CPC forces teams to map what progress actually means to the customer, rather than projecting internal assumptions of value.

5. Forces of Progress: Why Change Happens

5.1 The Push–Pull–Anxiety–Habit Model

Another foundational influence is the “Forces of Progress” model (Christensen, Cook & Hall, 2005). This model explains adoption as a balance of forces:

Push: dissatisfaction with the current situation

Pull: attraction toward a new solution

Anxieties: fears related to switching

Habits: inertia of the current behavior

The CPC incorporates this logic to help teams understand why customers stay stuck, even when a solution appears objectively better. Progress is not about rational optimization; it is about overcoming resistance embedded in routines and risk perception.

This aligns with behavioral economics (Kahneman, 2011), which demonstrates that human decision-making is biased, loss-averse, and context-sensitive.

6. Products as Value Delivery Tools (VDTs)

6.1 Reframing the Role of the Product

A central philosophical stance behind the CPC is the idea that a product is not the value itself, but a tool that enables progress. This resonates with service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004), which defines value as co-created in use rather than embedded in artifacts.

From this perspective:

Value does not exist at purchase

Value emerges during use, in context

Products succeed when they reduce friction in the progress journey

The CPC helps teams design products as Value Delivery Tools (VDTs)—artifacts whose sole purpose is to help customers move from their current state to a desired future state.

7. Structure and Logic of the Customer Progress Canvas

While variations may exist, the CPC is logically structured to follow the natural flow of human action:

Context – What situation triggered action?

Desired Progress – What does “better” look like for the customer?

Current State & Frictions – What is blocking progress?

Forces – What pushes, pulls, anxieties, and habits are at play?

Value Criteria – How will the customer judge success?

Implications for Design – What must the product enable, reduce, or avoid?

This mirrors cognitive models such as the perception–thought–action loop (Neisser, 1976), emphasizing that action emerges from interpreted context, not isolated needs.

8. From Insight to Design Decisions

Unlike analytical frameworks that end at insight, the CPC is explicitly decision-oriented. It is designed to inform:

Value proposition design

Feature prioritization

Go-to-market narratives

Experiment design

By anchoring decisions in customer progress, teams avoid the trap of feature accumulation and instead focus on reducing friction in the progress journey.

9. Positioning the CPC in the Academic Landscape

The Customer Progress Canvas does not replace existing theories; it integrates and operationalizes them. Its contribution lies in:

Synthesizing JTBD, design thinking, and behavioral science

Making context explicit and structured

Translating abstract theory into a usable design tool

In this sense, the CPC functions as a boundary object (Star & Griesemer, 1989): flexible enough for practitioners, rigorous enough to remain theoretically grounded.

10. Conclusion: Designing for Progress, Not Personas

The CPC represents a shift in how we understand customers, value, and products. It challenges teams to move beyond static personas and problem lists toward a deeper understanding of human progress in context.

By grounding design decisions in how people actually navigate change, uncertainty, and aspiration, the Customer Progress Canvas offers a more realistic—and ultimately more humane—foundation for innovation.

Key Academic References (Indicative)

Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma

Christensen, C., Cook, S., & Hall, T. (2005). Marketing Malpractice

Christensen, C. et al. (2016). Competing Against Luck

Suchman, L. (1987). Plans and Situated Actions

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1998). Contextual Design

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception

Norman, D. (2004). Emotional Design

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow

Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2004). Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Boundary Objects

Comments